|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home > Info Centre > Publications > Alert 2000 > Preserving Honour and the Warrior Spirit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Jamaica’s early inhabitants, the Arawaks, lacked the military means to ensure their security. They were conquered and enslaved by the Spaniards. The Spaniards in like manner made inadequate defence preparations and so lost Jamaica when challenged by a superior force. The British, the new power, on the other hand, came to value Jamaica like a pearl in the monarch’s crown. They established forts, positioned vessels at sea, garrisoned regular soldiers and artillerymen and raised a sizeable militia to repel invasions and suppress internal revolts. We learn from their experiences the importance of military security, to counter the threats to the way of life of a people. Profound social and political changes have taken place in the country over the years and these have impacted on the development of the military. The race, class and nationality of the men and women in the military have changed. What we hope to preserve in the Jamaican soldier today, is the same sense of honour and the spirit and courage of a warrior, which are a part of the heritage handed down by those who served before The military traditions bequeathed to the present day Jamaican soldier are at least bipolar in origin. Firstly there is the influence of our British colonial masters, who for three centuries had responsibility for the military security of the island, and then continued since Independence providing education and training for our troops. Secondly we should not dismiss the contribution of General Cudjoe and his captains of African ancestry. Their actions helped shape the course of military developments on the island. The majority of our soldiers today is of African descent and may be regarded as sons and daughters of ‘Cudjoe’ and ‘Nanny’. There is certainly more than a trace of the African warrior blood within the heart of the Jamaican soldier. The worth of the military has been proven repeatedly. As soldiers we can recall with pride the courageous defensive battle fought at Carlisle Bay in 1694 when a vastly out-numbered detachment from the Militia, successfully defended against the French invaders1. One of the sterner challenges faced by the military in Jamaica came from encounters with the freed slaves. These encounters gave evidence of the courage and skill in the art of warfare shown by our own forefathers of African descent, of whom we can be equally proud.

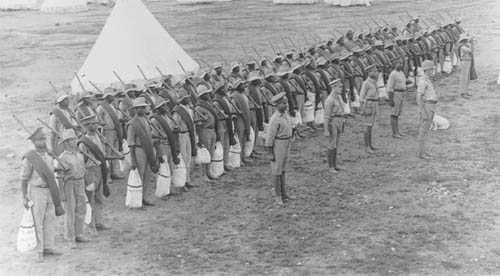

General Cudjoe’s army challenged the armed forces of the Crown for eleven years between 1728 and 1739, in what became known as the First Maroon War. The valour of these warriors of African descent, fighting with Cudjoe and Nanny, can be appreciated when it is considered that the total force engaged in suppressing them, out numbered them by more than ten to one4. The Maroons struggled to preserve their dignity and honour, the freedoms they had won, and their right to practice their traditions. The colonizers fought to preserve their own honour, their way of life and their investments in the land. In the spirit of the African fathers, General Cudjoe’s army forced its vastly superior opponents to admit to the impossibility of defeating the Maroons. Cudjoe could therefore sue for peace on agreeable terms with the British who had witnessed first hand the "unconquerable courage" of the black warrior. The British had no option but to admit black men into the militia in significant numbers. In 1792 black men comprised about a quarter of the over eight thousand men in the militia5. Without them, the strength necessary for the security of the island could not have been met. By the middle of the 19th Century, the worth of the black man as a disciplined soldier should have been beyond debate. Yet he had not gained the recognition he deserved as a part of the British West India Regiment (BWIR). We have reason still to be proud of the BWIR. The majority of the junior ranks was black, and had the same warrior spirit and traces of the African blood that possessed Cudjoe and Nanny. It is no surprise that a black Jamaican was a recipient of the most prestigious Victoria Cross, the highest honour awarded by the British Monarch for individual acts of valour in combat. It seems fair to assume that such inspiration came from Cudjoe and his troops. The War Office kept the Regiment out of battle in World War 1 for a long time. They opted to employ WIR battalions as labour battalions, much to the annoyance of soldiers who desired to face combat6. Sure enough, when the First and Second Battalions faced battle in Africa, Italy and Palestine, the units wasted no time in securing battle honours. Citizens who have observed and studied the military have come to respect the institution that we have today–the Jamaica Defence Force. At the most basic level of the Force however, where boot strikes ground, where finger grips trigger and where warrior interfaces with citizen, stands an individual. A confident, honourable, and fearsome soldier, we hope. Regrettably, there have been some glaring and embarrassing instances where individuals have breached military discipline and our sense of honour. The Jamaican people expect that such incidents would be few and further, that our noble institution would be duty bound to call offenders to account, and discharge anyone who unreasonably sullies the military’s good name. The institution is bigger than any member is. We must do what is necessary to preserve honour. Today our officers and men continue to be formally schooled in the British tradition. It is an education that could be balanced by a fuller appreciation for the valour and the historical contribution of the Jamaican soldier. Until this aspect of our military education is formalized, we may have to rely on the oral tradition. This is possible because ‘our young ones are born before the old ones die’. Traditions, legends and myths may thus be passed down to ‘Generation Next’. The lessons from our history are convincing enough on the question of the need for military security. Being out-numbered, out-gunned and under resourced may sound distressing, but this does not mean that victory will of necessity elude the numerically weaker party. Leadership, courage, honour, discipline and integrity are all "force multipliers." We have a proud heritage from both the British and our African forbears requiring us to stand up and fight with valour and with honour, and to pursue peace on worthwhile terms.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

General Cudjoe first organized his

army of freed slaves when it became evident that they were being pursued by a strong

contingent of regular troops and militia along with other hired hands, all promised

significant incentives for killing or capturing rebellious slaves2. General Cudjoe was

described as a bold, skilful and enterprising man. He was able to build a cohesive unit

out of the freed slaves who settled in remote villages. Cudjoe’s sister, Nanny, was also

undoubtedly a brave leader. To her was attributed "the supernatural power of

attracting the bullets of white soldiers to her posterior where they were caught and

rendered harmless"3.

General Cudjoe first organized his

army of freed slaves when it became evident that they were being pursued by a strong

contingent of regular troops and militia along with other hired hands, all promised

significant incentives for killing or capturing rebellious slaves2. General Cudjoe was

described as a bold, skilful and enterprising man. He was able to build a cohesive unit

out of the freed slaves who settled in remote villages. Cudjoe’s sister, Nanny, was also

undoubtedly a brave leader. To her was attributed "the supernatural power of

attracting the bullets of white soldiers to her posterior where they were caught and

rendered harmless"3.